Yan Petrovsky, a militant of the neo-Nazi Group "Rusich," will be deported to Russia from Finland. Finnish border guards have detained neo-Nazi militant and co-founder of the Russian sabotage-assault group "Rusich" Yan Petrovsky at the exit from Vantaa Prison, the Helsingin Sanomat newspaper reported. Earlier, the Supreme Court of Finland ruled that Petrovsky could not be extradited to Ukraine, where he is suspected of forming a terrorist group, because he could allegedly face torture in a Ukrainian prison, and called for his release. In August, Petrovsky, with a passport in the name of Voislav Torden, was detained by the Finnish Border Guard agency while trying to fly to Nice, following an extradition request from Ukraine. "Rusich" group is fighting on Russia's side in Ukraine. Petrovsky was one of its commanders. He became famous for posing in front of the corpses of Ukrainian soldiers. Since 2004, "Slavyan" lived in Norway, but in 2017, he was stripped of his residence permit and deported. In September 2022, the United States imposed sanctions on him.

|

|

|

“If by chance you were to ask me which ornaments I would desire above all others in my house, I would reply, without much pause for reflection, arms and books.”

Baldassare Castiglione |

|

Originally Posted By lorazepam: I posted these several pages back. they are available from china, around 300 bucks a pop. They work very well for their size. View Quote View All Quotes View All Quotes Originally Posted By lorazepam: Originally Posted By AlmightyTallest:

The thermal imagers. https://pbs.twimg.com/media/GAv7-tzWQAAYrm7?format=jpg&name=4096x4096

Rather easy of the shelf thermal for use in FPV's. Review of that thermal system here: https://hothardware.com/reviews/infiniray-p2-pro-thermal-imaging-camera-for-smartphones-review I posted these several pages back. they are available from china, around 300 bucks a pop. They work very well for their size. I remember that, just impressive to see a turnkey USB thermal plug in for night work with fpv drones. |

|

|

It's not stupid, it's advanced!!

|

|

Originally Posted By lorazepam: I would hope they are building them themselves. I put together a few for ham radio use. BMS is about 4 dollars, depending on the batteries, 3-10 bucks each. Shrink tube, silver straps, and a bit of wire and an xt60 connector. I wouldn't worry about balancing cells for a 1 way trip like that. I got caught up finally. Death has been touching the lorazepam household too much lately, including my dog Lady last night. Thanks for the thread to get my mind off of things for a while. View Quote View All Quotes View All Quotes Originally Posted By lorazepam: Originally Posted By planemaker: That box full of batteries probably cost them more than all those airframes put together. That, and they probably still have to add the EW-resistant links and cameras. That kind of stuff isn't "cheap" but it's not mil-spec expensive either. I would hope they are building them themselves. I put together a few for ham radio use. BMS is about 4 dollars, depending on the batteries, 3-10 bucks each. Shrink tube, silver straps, and a bit of wire and an xt60 connector. I wouldn't worry about balancing cells for a 1 way trip like that. I got caught up finally. Death has been touching the lorazepam household too much lately, including my dog Lady last night. Thanks for the thread to get my mind off of things for a while. Sorry to hear about your dog, and other troubles. |

|

|

It's not stupid, it's advanced!!

|

|

This is allegedly an image of an Su-57 taking a smoke break.

https://twitter.com/TreasChest/status/1733203160116699544 |

|

|

“If by chance you were to ask me which ornaments I would desire above all others in my house, I would reply, without much pause for reflection, arms and books.”

Baldassare Castiglione |

|

View Quote SU57? What’s going on? |

|

|

|

|

It is amazing they could never hit a Himars or M270 yet.

|

|

|

It's not stupid, it's advanced!!

|

|

Originally Posted By Prime: This is allegedly an image of an Su-57 taking a smoke break. https://pbs.twimg.com/media/GA2TFmGWAAA1SnX?format=jpg&name=large https://twitter.com/TreasChest/status/1733203160116699544 View Quote   Awww, they are saying it might just be de icing.

|

|

|

It's not stupid, it's advanced!!

|

|

Originally Posted By Lieh-tzu: This point was raised in another thread. The strategic leadership has been woefully deficient in long-term planning & thinking, particularly in production & procurement. Industry consolidation has been allowed to the point where not just a single plant, but sometimes a single component or production tool is used/available for critical items/systems. As you point out, usage is maximized for the purpose of efficiency, but that doesn't permit surge capacity. IMO, procurement contracts need to be structured in a way that not only requires contractors to maintain surge/excess production capacity, but also better maintains multiple/competing suppliers to increase redundancy. Can you imagine how screwed the DoD would be if the Watervliet Arsenal were hit with a missile salvo? It would take years to recover. View Quote If you don’t pay for plants to stay open they will close. |

|

|

|

|

Originally Posted By AlmightyTallest:  https://media3.giphy.com/media/v1.Y2lkPTc5MGI3NjExdmhkNzdkYnVyZnl2cXhpeWg4aXJmdXl2MHhyd2s5aXgwNWtvcjEwNiZlcD12MV9pbnRlcm5hbF9naWZfYnlfaWQmY3Q9Zw/F1YAijzu9X62Q/giphy.gif Awww, they are saying it might just be de icing.

View Quote Yeah, I found a pro-Russian account that says it's "engine heaters". Figures, it's Russian, it's gonna make that much smoke even if it's working properly  |

|

|

“If by chance you were to ask me which ornaments I would desire above all others in my house, I would reply, without much pause for reflection, arms and books.”

Baldassare Castiglione |

|

|

|

“If by chance you were to ask me which ornaments I would desire above all others in my house, I would reply, without much pause for reflection, arms and books.”

Baldassare Castiglione |

|

Originally Posted By Jaehaerys: Some very interesting information regarding drones from a Ukrainian intel officer I'm stalking (@planemaker may find this stuff interesting): View Quote View All Quotes View All Quotes Originally Posted By Jaehaerys: Some very interesting information regarding drones from a Ukrainian intel officer I'm stalking (@planemaker may find this stuff interesting): I've never seen a mythical Switchblade, but in general it is as you say - the main difference is a sheer difference in price and scale (of availability first and foremost). The FPVs are used in tens of thousands monthly, certainly more than Switchblades were ever produced. Looking at basic Switchblade 600 specs, you should rather compare them to Lancets, which they resemble much more. Tactic-wise, Switchblades have longer range, a more sophisticated control channel, safer to handle, and come assembled to key, probably with a factory warranty. FPVs are crafted from a wide array of vaguely standardized, mass-produced components, which have to be assembled by the user in kits, including a frame, the engines and rotors, a control chip and software (which can be programmed by the user in many ways or even written from scratch), a battery, RC antennas and a camera, and finally a delivery parcel - which is usually duct-taped and armed manually moments before flight. The whole thing has to be properly tested and balanced together to achieve desirable specifications. The specifications themselves are thus extremely varied, and depend on anything starting from your desired goals, quality of the components and assembly, etc. But thus is their strength - FPVs are extremely flexible. Jamming them might be extremely hard, even though they use cheap and weak Chinese radio components - because they have non-standard operating frequencies, and because the users can ad-hoc modify them in a field with both external and internal features. They can carry a wide array of ammunition (usually up to 3 kg), a recent modification is a Claymore (МОН-50) mine for devastating AP effect. Finally, they are much more maneuverable, being copter-type, and in the hands of the skilled pilot can get in the tightest holes, firing ports, or target a weak spot on a moving vehicle from weird angles. But the greatest difference is still a price and availability. When Switchblades come in tenths of thousands a month, then we can put them on the same scale to compare. Different types of drones are vulnerable (or resistant) to different types of jamming. Basic DJI\Autel and similar drones operate on specific standard frequencies, and since they were meant to be compliant to governmental regulations, they were made vulnerable to EW on purpose. The handicaps can be mostly fixed, but the standard frequencies meant that commercial\military EW contractors built their production lines for the signal jammers to these drones. However FPVs are made using a wide variety of non-standard radio parts (control channel is often in between 840-1300Mhz for example), and there are currently no effective "military-grade" jammers available - the R&D and procurement simply can't keep up. And by the time they catch up, FPVs will move to other frequencies (they already do). Most of anti-FPV jammers have to be of the dome-type - all-round emitters with relatively short range. Currently the main source for all parts is China - they produce stuff like this en masse. You stack'em up, attach appropriate antennas and power units, and there you have your magic voodoo force field. However currently it is about 20-30% effective against incoming FPVs. Also when its on, it emits like crazy so that enemy electronic surveillance can spot that in a matter of minutes with ~100m accuracy, which may bring unnecessary attention. Of course it is a bit more complicated than that to explain in a single post - many radio-nerds on both sides of this war are working hard to create a solution that can be effective and scaled up. There is about a dozen honest and significant EW startups in Ukraine that have done some great work on this. I personally (though by no means a radio-nerd myself) assisted at least one of them to start things up. However they all receive exactly zero help and instead lots of hindering from the government. So we can't set up large production like the russians, that have a direct state supervision and mass production. Currently the russians outnumber us ~10:1 in the number of active anti-FPV EW shields (though again with ~30% or worse efficiency), and they also were first to create a more significant and powerful area jammers specifically against FPVs. But in this fight, classic EW is doomed to fail sooner or later, since AI-integration is rapidly moving forward and basic targeting assist is already in use. Once its more or less autonomous, I feel sorry for us meatbags. Very interesting, thanks for posting. One of the big issues with having a bunch of ad-hoc RF endeavors is that when one group finds the rooskie EW effective, that may not get relayed to other groups to change frequencies. In addition, the Ukrainian EW folks may be behind the 8-ball on which frequencies friendly forces are using, causing RF fratricide. Technology cat and mouse games are exceptionally difficult in that there is no "winner" as such. It's always time dependent as to who has the upper hand. The only thing that I think the Ukrainians have the upper hand with is rapidity of innovation. They can develop and implement a solution much faster than it appears the rooskies can. Sanctions will also come into play here at some point. |

|

|

|

|

Originally Posted By lorazepam: I would hope they are building them themselves. I put together a few for ham radio use. BMS is about 4 dollars, depending on the batteries, 3-10 bucks each. Shrink tube, silver straps, and a bit of wire and an xt60 connector. I wouldn't worry about balancing cells for a 1 way trip like that. I got caught up finally. Death has been touching the lorazepam household too much lately, including my dog Lady last night. Thanks for the thread to get my mind off of things for a while. View Quote Sorry for your loss. Dogs are family and it sucks to lose them. |

|

|

DeSantis 2024

Warmonger |

|

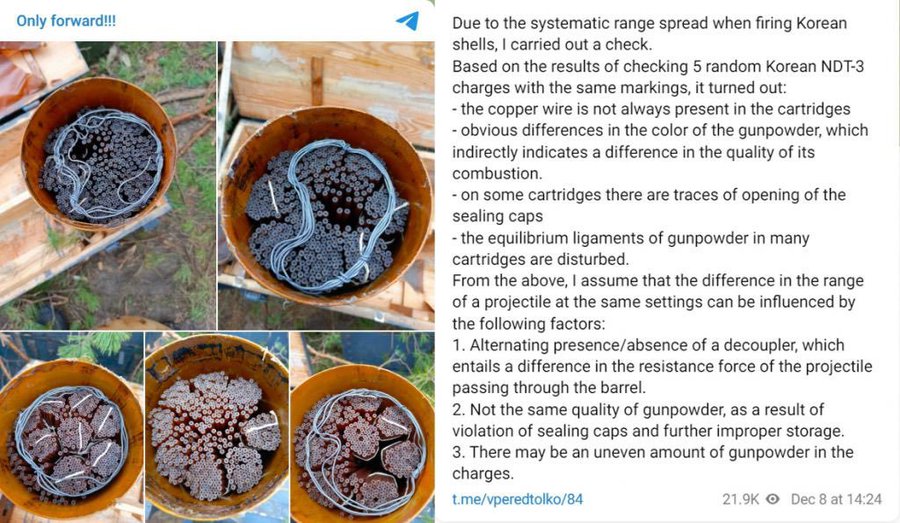

North Korean ammo has issues, Russian source.

|

|

|

It's not stupid, it's advanced!!

|

|

Lorazepam, so sorry to hear about the loss of your dog, She looked beautiful and had a good home with you. Scott

|

|

|

|

|

Originally Posted By Prime: https://pbs.twimg.com/media/GA2bbs2W8AAH73l?format=jpg&name=large View Quote |

|

|

nothing of value here

|

|

Putin faces growing threat from the wives and mothers of mobilized soldiers

The grass-roots movement poses a real challenge in the run-up to Russia’s March 2024 presidential election. In Russia, the wives, mothers and other relatives of mobilized soldiers have become a growing thorn in the Kremlin’s side. Through protests, appeals and petitions, they have expressed their mounting anger at the Russian state for not allowing mobilized soldiers to return home from Ukraine. Russia’s political leadership faces a stark choice between placating this increasingly vocal movement and maintaining troop numbers in its war on Ukraine. Unpopular mobilization On 21 September 2022, President Vladimir Putin announced a ‘partial mobilization’, allowing the Russian military to call up around 300,000 reservists. As Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine turned into a lengthy war, the mobilization was needed to meet the Russian military’s personnel needs. But the move was deeply unpopular. Many Russians – especially young men – fled the country to avoid being called up. Thousands were arrested for protesting against mobilization – and Putin’s approval rating took a clear hit. The end of mobilization was announced in late October 2022. This meant, in principle, that the state would stop calling up reservists. But Putin did not sign a decree formalizing the decision, leading to uncertainty and speculation regarding the future of mobilization. An organization named the ‘Council of Mothers and Wives’ was set up following the announcement of ‘partial mobilization’. Its goal was to coordinate activities across the country by relatives of those mobilized, including pressuring the authorities to resolve issues such as men being called up illegally or being given faulty equipment. The council tried to engage directly with Putin but its members were rebuffed. Instead, the Kremlin organized a staged meeting in November 2022 with participants apparently picked for their pro-regime track record. Demonstrating the hopelessness of civil society mobilizing against military mobilization, the council was labelled a ‘foreign agent’ in May of this year and subsequently closed in July. But that was not the end of the story. Endless mobilization More than a year after ‘partial mobilization’ was announced, grievances were growing about ‘endless mobilization’. When asked in September 2023 at what point mobilized soldiers would be allowed to return home, Colonel General Andrey Kartapolov – chairman of the Duma’s defence committee – said ‘after the end of the special military operation’. There was, therefore, no end in sight. Connected via social media, a growing informal regional network joined together wives and other relatives of the mobilized. This grassroots movement is united by a simple goal: to secure the return of their loved ones. On 7 November, some members of this nascent movement joined a rally organized by the Communist Party of the Russian Federation in central Moscow. The decision to join an existing event was an effective way of circumventing the dramatic crackdown on dissenting voices and protest seen across Russia over the past few years, particularly since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Applications by regional groups of the movement to hold standalone protests have been rejected in most cases, with the authorities citing COVID-19 restrictions. But that has not stopped coordination online. Pressure on Putin The movement has framed itself as being non-political. A manifesto published on 12 November on the Telegram channel ‘The Way Home’ said it was ‘not interested in rocking the boat and destabilizing the political situation’. The movement is, crucially, not anti-war – it is anti-mobilization. And one of the reasons it presents such a threat is that its participants include people from Putin’s support base. But the reaction from the Kremlin was silence. On 27 November, ‘The Way Home’ published an ‘appeal to the people’, along with a petition allowing individuals to add their signature in support of the movement’s manifesto. The language was now more visceral – ‘we are being betrayed and destroyed by our own’ – and directly mentioned Putin. The appeal refers to the president’s past broken promises, limiting his ability to deflect blame to lower-level officials. It notes that Putin has decreed 2024 to be the ‘year of the family’ in Russia – and the bitter irony of this, when ‘wives wail without their husbands, children grow up without their fathers, and many have already become orphans’. The text also notes the president’s ‘sense of humour’ when mobilized men are being made to stay in the conflict indefinitely, but prisoners can secure their freedom by fighting for mere months. Zugzwang The Kremlin is in a lose-lose situation. If it allows mobilized soldiers to return home, it will face an acute shortage of troops. That might necessitate a second – even more unpopular – mobilization, which could lead to even more social strife. But if the authorities don’t allow the soldiers to return home, they face the growing ire of an influential section of Russian society – including previously loyal supporters of Putin and the system he has created. The optics of cracking down on wives pleading for their husbands’ lives would also not be good in the run-up to the presidential election, scheduled for March 2024. That explains the variety of attempts made to diffuse the movement, from intimidation to trying to buy off participants. The Telegram channel ‘The Way Home’ has been labelled ‘fake’ in an attempt to discredit its content, along with local groups. According to the Russian investigative website The Insider, regional governors have been instructed to prevent the movement’s activities spreading ‘to the streets’ in the run-up to the March presidential election – at ‘any cost’. But a key challenge for authorities is the organizational structure of the emerging movement. The links joining together relatives of mobilized soldiers are horizontal; there is no top-down structure for the Kremlin to focus on, isolate and destroy. "The Russian government now appears trapped between the rhetoric of support for what it calls ‘traditional values’ and the pleas of wives and mothers to protect their loved ones". Vyacheslav Volodin, speaker of the State Duma – the lower chamber of the bicameral national legislature – has said that supporting families will be a priority for the Duma in 2024. But the Russian government now appears trapped between the rhetoric of support for what it calls ‘traditional values’ and the pleas of wives and mothers to protect their loved ones. How this tension will play out during the presidential campaign remains to be seen. https://www.chathamhouse.org/2023/12/putin-faces-growing-threat-wives-and-mothers-mobilized-soldiers |

|

|

“If by chance you were to ask me which ornaments I would desire above all others in my house, I would reply, without much pause for reflection, arms and books.”

Baldassare Castiglione |

|

Originally Posted By ITCHY-FINGER: I was wondering what caused that pattern of craters. Daisy-chained mines? Sympathetic detonations? There are new mines in rows just outside the craters that must be newly emplaced. View Quote View All Quotes View All Quotes Originally Posted By ITCHY-FINGER: Originally Posted By 4xGM300m: Old pictures from September? that were postet here many times. Look at the distinctive pattern where the mines exploded near the two BTRs. https://www.ar15.com/media/mediaFiles/201300/GAvwbsNXEAAKD8u_jpg-3053006.JPG I was wondering what caused that pattern of craters. Daisy-chained mines? Sympathetic detonations? There are new mines in rows just outside the craters that must be newly emplaced. Something I bet that both sides are doing is laying these surface minefields to cover a lot of space with limited manpower, but then also laying buried minefields. So they clear the obvious minefield using drone spotting, then run over another minefield they didn’t know about. |

|

|

|

https://beyondparallel.csis.org/activity-at-najin-points-to-continued-dprk-russia-arms-transfers/ |

|

|

“If by chance you were to ask me which ornaments I would desire above all others in my house, I would reply, without much pause for reflection, arms and books.”

Baldassare Castiglione |

|

Originally Posted By Prime:

View Quote I hope they missed a zero there. |

|

|

|

|

Originally Posted By ITCHY-FINGER: I was wondering what caused that pattern of craters. Daisy-chained mines? Sympathetic detonations? There are new mines in rows just outside the craters that must be newly emplaced. View Quote View All Quotes View All Quotes Originally Posted By ITCHY-FINGER: Originally Posted By 4xGM300m: Old pictures from September? that were postet here many times. Look at the distinctive pattern where the mines exploded near the two BTRs. https://www.ar15.com/media/mediaFiles/201300/GAvwbsNXEAAKD8u_jpg-3053006.JPG I was wondering what caused that pattern of craters. Daisy-chained mines? Sympathetic detonations? There are new mines in rows just outside the craters that must be newly emplaced. My bet is on sympathetic detonations. |

|

|

„From a place you will not see, comes a sound you will not hear.“

Thanks for the membership @ toaster |

|

Originally Posted By Capta: I hope they missed a zero there. View Quote View All Quotes View All Quotes Originally Posted By Capta: Originally Posted By Prime:

I hope they missed a zero there. I guess SMart or something else special. |

|

|

„From a place you will not see, comes a sound you will not hear.“

Thanks for the membership @ toaster |

|

|

|

“If by chance you were to ask me which ornaments I would desire above all others in my house, I would reply, without much pause for reflection, arms and books.”

Baldassare Castiglione |

|

https://twitter.com/DanCrenshawTX/status/1732919328230477889

The Dens continue to take every opportunity to miss an opportunity. |

|

|

|

|

Thanks everyone. She was a good pup, but I knew yesterday we may have to have the vet put her down, but she went in her sleep in her favorite bed. I would trade 50 miles of trails and fields for 100 yds to give her a proper goodbye. Still have my buddy Walter, another semper fi rescue, and the wife's cat that thinks I belong to her. It never gets easy, they steal your heart and their lives are far too short.

|

|

|

World ain't what it seems, is it Gunny?

|

|

Putin’s War Party

How Russia’s Election Will Validate Autocracy—and Permanent Conflict With the West  If there is Putin, there is Russia; if there is no Putin, there is no Russia,” the current speaker of the State Duma, the aggressive loyalist Vyacheslav Volodin, pronounced, back in 2014. He was outlining an ideal autocracy, one in which the country would be equated with its ruler and vice versa. At the time Volodin spoke those words, the Kremlin was basking in an upsurge of national euphoria following the annexation of Crimea. With the so-called Putin majority ascendant, the government could hasten its shift toward such a regime with broad popular approval. But Volodin was a bit ahead of his time. It was not until the 2020 constitutional reform, which “reset” Russia’s presidential term limits and solidified Putin’s mature dictatorship, that his formula was codified in the country’s institutions. And it was in 2022, with the beginning of the “special operation” in Ukraine, that the propaganda meaning of “Putin equals Russia” became starkly apparent. As the Kremlin would have it, Putin’s war is Russia’s war, and by extension, a war involving all Russians—a fanciful notion that not only plays into the hands of regime propagandists but which has been readily embraced by many Western officials, as well. Of course, the real picture is far more complex. By now, the Putin majority has long since been taken as a given, and no one talks about it anymore. Instead, there is the pro-war majority, which supports the war partly by ignoring it in everyday life. As for the anti-Putin minority, the Kremlin’s long-standing habit of treating with contempt any who dare oppose the president has been transformed into a policy of active persecution and denunciation. Opposition and civil society figures themselves have been systematically discredited, exiled, and eliminated. Nonetheless, Putin still needs elections to give legitimacy to his eternal rule—and to his unending war. Thus, in March 2024, he will run for president for the fifth time since 2000. And as a result of the 2020 reform, it may not be the last, either. According to the changed constitution, Putin will able to run for office twice more—in 2024 and 2030—meaning that he could rule until 2036, when he will be eighty-three years old. For now, it seems clear that Putin is ready to make full use of that opportunity, at least in the coming vote. But this time, with the war in the background, there are new rules to the game, and both Putin and the Russian public know them. In exchange for keeping most of them out of the trenches, the passive majority of Russians will continue to support the government. And the elections—or rather, the mass approval of Putin’s activities—will show that the people, at least, are playing along. Ballots have become currency: Russians think that they can buy their own relative tranquility with them, even though there are no guarantees that Putin will keep his side of the bargain. JUST SAY YES Given the complete lack of alternatives to Putin, some of his supporters, such as the Chechen leader and fierce loyalist Ramzan Kadyrov, have proposed canceling the 2024 election altogether. Wouldn’t it be easier to forgo the vote, on the grounds that the country is at war, and that in any case, the Russian political field has been comprehensively cleared of competitors? Or why not elevate Putin to the title of supreme leader, national leader, or tsar, and then elect a formal president? But Putin really needs elections, at least in theory. In addition to refreshing his legitimacy, they serve as a way to show that the opposition—through the predictable landslide outcome—remains a tiny minority and cannot go against the overwhelming will of the Russian people. Moreover, by voting for Putin in 2024, Russians will legitimize his war. Even if the active phase of that war ends someday, it will still need to continue through permanent confrontation with the West and as a rationale for unrelenting repression, suppression, and censorship at home. Rather than elections, then, the March vote should be thought of as a kind of acclamation for the leader: they are simply voting yes to the only real choice available. Technically, this is a legitimate form of democratic expression, as enshrined in the constitution—and, apparently, in Russian history. (New textbooks for schools and universities discuss such Russian political traditions as the Novgorod veche, or popular assembly, in which everything was decided by shouting, approval, and acclamation by the crowd.) In other words, in the absence of any political competition, the regime has everything to gain from a fresh acclamation of its rule, and little to lose. Putin’s high numbers are guaranteed. Some will vote for him out of a sense of falsely understood civic duty, some will be coerced to do so at work: such is the general state of paranoia in today’s Russia that people sometimes take a smartphone picture of their completed ballot and send it to their bosses, after which they get the right to return to their private lives. Other votes may be falsified, including, perhaps, with the help of electronic voting systems. Still, deciding what content to fill the campaign with is another question. Obviously, it is essential for Putin to consolidate his narrative about the war. As Putin likes to say, “It was not us”: Russia was attacked by the West, and in response began a “national liberation struggle” to free Russia and other peoples enslaved by the West. And since Russians find themselves in a besieged fortress, they must give full support to their commander to repel both the enemy at the gates and the traitors and foreign agents within. By now, this logic has acquired the status of an axiom. Along with it comes a series of arguments—Russia is fighting for a “fairer multipolar world,” Russia is a special “state-civilization”—that justify the war, why it cannot end, and Putin’s rule itself. But what new element can be brought into the current election campaign, except, of course, an abstract declaration of peace and victory? STORIES ABOUT WHEAT In theory, the Russian public does not attach much significance to elections. In the minds of most people, there is simply no alternative to Putin, even if they think he is not particularly good. When Russians say “Putin,” they mean the president, and vice versa; like a medieval king, Putin has two bodies—one physical, one symbolic. Putin is the collective “we” of Russians, and voting for him every few years has become a ritual, like raising the flag or singing the national anthem on Mondays in high schools across Russia. But the war has added a new dimension to this rite. During the “special operation,” an unwritten agreement has been established between the people and their leader. The gist of this special relationship is that as long as the state refrains from dragging (most) people into battle, Russians will not question Putin’s authority. The partial mobilization in the fall of 2022 briefly called into question the state’s promise, but since then the authorities have largely solved the problem. Essentially, they have demobilized Russians psychologically, by maintaining and enforcing a pervasive normality. Thus, Putin himself has focused almost exclusively on domestic issues such as addressing economic problems and supporting artificial intelligence, staging meetings with young scientists and talented children. As a result, during the second year of the war, the general mood of the population has been much better, even despite rumors about another possible military mobilization after the election. One darker cloud has appeared over the Kremlin, in the form of open disgruntlement from families of the men who were mobilized in October 2022. These families are not seeking money, but they want to bring their sons and husbands home. They sense injustice, given that real criminals and brutal killers, who were pulled out of prison to fight in the war, have to serve for only six months before they can return as heroes, while their own sons have been given no reprieve. The government does not have a convincing answer to this challenge: Putin has long been used to fighting the intelligentsia and the liberal opposition, but here he is dealing with discontent from his own social base. These soldiers’ families have not yet coalesced into a formal movement or taken an explicit antiwar stance—a step that would be impossible because of the high level of repression. But every day these families have become more and more politicized.  For the bulk of the population, however, it is enough for the government to regularly tout the country’s economic health and income growth, and the mere fact that the country is not experiencing economic and social collapse is enough to convey an impression of business as usual. The Kremlin also continually highlights its foreign policy “successes.” In this imaginary world, Russia is supported in its confrontation with the West by the “global majority” in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. They are not just allies but countries for whom Russia is a ray of light in the gloom. It is assumed that anti-Western rhetoric and offers of economic assistance—or, as in the case of Africa, grain—will automatically lead the former satellites of the Soviet Union back to Russia. Meanwhile, official Russian media reports about military operations tend to emphasize the continual successes of “our guys” at the front. In these sunny accounts, there are no serious losses, only heroic behavior and victories. These briefings have come to resemble Soviet reports on agricultural achievements: the battle for the harvest is going well, and the only possible feeling can be one of satisfaction. From a Western point of view, these fantasy narratives seem unlikely to convince anyone. Surely, Russians must be sensitive to their growing isolation and economic hardship, and the ever-growing sacrifice of their young men at the front. But the Putin regime is not built upon active support. All it requires is the indifference of the majority, who mostly find it easier to accept the picture of the world that is imposed from above. By embracing the Putin story, they can retain a sense of moral superiority over a West that, they are told, is seeking to dismember their country, just as Napoleon, Hitler, and the “American imperialists” did in past decades. From month to month, Russian sociologists report broadly the same findings. Attention to events in Ukraine has stagnated; less than half of respondents say they follow the war closely, according to surveys by the independent Levada Center. On average, their support for the military remains high: about 75 percent of respondents say that they support the actions of the armed forces, including 45 percent who express “strong support.” On the other hand, surveys consistently show that slightly more than a half of respondents favor starting peace negotiations than continuing the war. But since the country has made large sacrifices in the fighting, most of those supporting a settlement would like to get something in return: Russia should keep the “new” territories it has conquered or “restored” to Moscow. BACK IN THE USSR Having reframed the “special operation” in Ukraine into a multidimensional war against the West, Putin has no particular urgency to talk about an endgame. In this sense, Putin’s goals for the war are no longer limited to returning Ukraine to Russia but now encompass what has become an existential rematch with the West, in which the Ukraine war is a part of a long, historically significant clash of civilizations. Putin sees himself as completing the mission begun by his historic predecessors, who were always forced to fight Western encroachment. In Putin’s new interpretation, even the Tatar-Mongol yoke—the two centuries of Russian subjugation that followed the invasion of Batu Khan, the grandson of Genghis Khan, in 1237—was not as harmful as Western influence and Western attacks. And since this is now an open-ended confrontation, the timeline for “victory” will necessarily extend far beyond the next decade. Ordinary Russians are receptive to ideas about the country’s historical greatness. As polling data have shown for many years, the main source of popular pride in the state today is the country’s glorious past. Russians have a special regard for their imperial history, especially the history of the Soviet Union, and an idealized image of the Soviet Union as a kingdom of justice has begun to emerge. At the same time, helped by acts of erasure by the Putin regime itself, Stalin’s repressions have receded from view or are sometimes considered as something inevitable and even positive. Among the Soviet achievements most remembered by Russians today, the greatest of all is the Soviet victory in the Great Patriotic War, as Russians refer to World War II. Accordingly, Putin has continually compared the “special operation” against Ukraine with the war against Nazi Germany. Thus, the celebrated soldiers and generals of the Great Patriotic War are the direct predecessors of today’s military, and by fighting in Putin’s war, Russians can again find redemption in heroic sacrifice. For example, in a speech before this year’s May 9 Victory Day parade, Putin suggested that the West was trying to reverse Russia’s historic victory. “Their goal,” he said, “is to achieve the collapse and destruction of our country, erase the results of the Second World War.” PEAK PUTIN? To make his worldview stick, however, Putin needs a viable economic model to sustain the mythmaking. In recent years, and especially since the start of the war, he has complemented his carefully cultivated distrust of the outside world by rejecting what he calls economic and technological “dependence” on the West. In practice, the Kremlin has been eliminating everything Western not through import substitution—which is impossible in a modern economy—but through a new dependence on China. Meanwhile, technology is becoming both more primitive and more expensive, which naturally puts the burden on the end consumer. Russia’s oil and gas resources—essential for sustaining the country’s extraordinary military expenditures—remain as important as ever. In a way, ideology is being used to make up for the shortfall in energy revenues, and to compensate for the gradual decline in the quality of life. Of course, the regime going to great lengths to maintain the impression that life goes on as normal, and to a degree, this is true: formally, in 2023, the country’s GDP and real incomes of the population are growing. But this is in large measure because of state injections into sectors serving the war and social payments to its participants. That growth is coming at the expense of the state, and it is unclear how long its resources will last. Risks of fiscal imbalance remain. A larger problem is the lack of an economic vision for the future. As the historian Alexander Etkind notes, “A resource-dependent state is always afraid of the raw materials running out, but the biggest threat of all comes from new technology that makes those materials unnecessary.” Putin has never believed in the energy transition or green economy, but by insisting on preserving Russia’s existing technological structure and petrostate model, his regime has impeded modernization in both a technological and political sense. As a result, the oil and gas economy is not being replaced by a more sustainable model. Notably, some of the countries in the east that are now consuming Russian raw materials may be shifting their energy mix in the future: in time, for example, China may have less demand for Russian energy. But Putin’s autocracy does not care about future generations, much less the environment. Alongside its dependence on nonrenewable fossil fuels, the Kremlin tends to treat human capital as another expendable commodity. But that does not make the human supply chain any cheaper. On the contrary, it is becoming more expensive: professional soldiers, mercenaries, volunteers, family members of the dead and wounded, and the workers who man Russia’s military-industrial complex (and of which there is currently a grave shortage) must all be paid. Hence, the government has had to reconcile itself to an inexorable growth of wages and social benefits. People’s incomes are growing not because of economic development or advances in the quality of the labor force but simply so the government can sustain hostilities and fuel the continued production of lethal weapons. For now, the state budget is still balanced, but budget discipline is in a permanent danger because of the state’s chosen priorities. By paying more for defense and security, Russia has fewer resources for people and their health and development. In the Putin economic model, more spending on death means that there is less to spend on life. SWAN LAKE So what will Putin’s election campaign look like? Given the current situation, Putin can only offer the public the same model of survival that has become standard since the “special operation” began: to live against the backdrop of war without paying attention to it and wait for “victory” in whatever form the president someday chooses. Again, it is unlikely that that choice will be clearly defined during the election season. The war itself has become a mode of existence for Putin’s system, and there is little reason to expect that it will end any time soon, since that could undercut the urgency of supporting him. In any case, during periods of peace, Putin’s ratings have often stagnated, whereas they have soared during moments of military “patriotic” hysteria such as the Georgian war of 2008 and the Crimea annexation. The “special operation” has been no exception. Moreover, for now, war fatigue has not yet translated into serious discontent or a decrease in support for the regime. According to the Levada Center, popular support for Putin, as well as for the war and the military, has remained broadly stable, with Putin maintaining around an 80 percent approval rating. In theory, then, the indifference of the pro-war majority suggests that Putin can continue the war for the indefinite future. The Kremlin’s other option would be to ramp up hostilities, including a new mobilization, whether partial or general, combined with further distancing from the West and more repression at home. But such changes could rock the Kremlin, which at some point risks colliding with an iceberg of extreme public anxiety and a deteriorating economy. Russia’s underlying problems are not going anywhere, and have been slowed down only by the relatively rational actions of the government’s economic managers. Accordingly, maintaining the status quo seems the most likely path forward. During periods of peace, Putin’s ratings have stagnated. When Russians go to the polls in March, Putin can count on high voter turnout and continued passive support for the war. Most of them have very low expectations: they have long lived according to the mantra “The main thing is that it shouldn’t get even worse.” But the fresh acclamation of the regime that the election will doubtless bring will not necessarily provide a mandate for truly drastic moves such as the full closure of Russia’s borders or the use of nuclear weapons. Indeed, as the Kremlin must understand, the outcome will be less a mandate for radical new changes than a signal that it can continue much as before. How long can a country exist in this state of passive and unproductive inertia? Theoretically, Putin could reap advantages by continuing the war but at the same time keeping the population calm, thereby outlasting the West with its supposedly flagging interest. But there are several reasons to question this assumption: first, it is not only Ukraine and the West but also Russia whose resources are being dramatically depleted. Second, surprises are possible, such as the growing wave of discontent among the Russian mobilized soldiers’ families. Even if it does not result in a broader political backlash, the phenomenon has already shown that black swans of different sizes can come from unexpected places at unexpected times. But where are the redlines that show just how far resources can be depleted and the patience of various sections of the population be tested without triggering a larger collapse? Do these limits even exist in Russia? So far, with a few minor exceptions, everything points to the fact that they do not. Moreover, no matter how much the regime has tightened its grip, change of leadership is not a priority for the Russian public: on the contrary, polls and focus groups show that many people fear a change at the top. Still, Russians are not ready to die for Putin. In 2018 and 2020, Putin’s ratings fell because of an unpopular decision to increase the retirement age, and then because of the effects of the pandemic; it is possible that his base of support will take other hits in the coming months. Indeed, in the mood of both the public and the elites, there is an invisible yet discernible expectation of such events. For most, however, the yearning is more basic. They desire to end “all this”—meaning get rid of war—as quickly as possible and begin to live better, more safely, and more peacefully. But it is unlikely that this will happen without regime change. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/russian-federation/putins-war-party |

|

|

“If by chance you were to ask me which ornaments I would desire above all others in my house, I would reply, without much pause for reflection, arms and books.”

Baldassare Castiglione |

|

Originally Posted By AlmightyTallest:

View Quote Satisfying boom... |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Originally Posted By RockNwood: Yeah, the defense industries like to scale back production as much as they can to ensure continuous 100% capacity. Lean and max margins. But that makes ramping up hard especially when they either sell off redundant factories or never built for large production to begin with. Part of the problem may be that “we only do super-duper premium stuff” with no concept of rapid large scale ramp. Fundamentally Congress and MIC have agreed on a slow and steady rate with no plans for a near peer war or assisting another country without getting involved ourselves in such. View Quote Committed and even desperate foreign buyers are paying for the fickleness of the US Congress changing priorities every 2 years. |

|

|

|

|

Originally Posted By Prime: Putin’s War Party How Russia’s Election Will Validate Autocracy—and Permanent Conflict With the West https://cdn-live.foreignaffairs.com/sites/default/files/styles/_webp_large_2x/public/images/2023/11/30/RTSPYNGB.JPG.webp?itok=0gvnAB7T If there is Putin, there is Russia; if there is no Putin, there is no Russia,” the current speaker of the State Duma, the aggressive loyalist Vyacheslav Volodin, pronounced, back in 2014. He was outlining an ideal autocracy, one in which the country would be equated with its ruler and vice versa. At the time Volodin spoke those words, the Kremlin was basking in an upsurge of national euphoria following the annexation of Crimea. With the so-called Putin majority ascendant, the government could hasten its shift toward such a regime with broad popular approval. But Volodin was a bit ahead of his time. It was not until the 2020 constitutional reform, which “reset” Russia’s presidential term limits and solidified Putin’s mature dictatorship, that his formula was codified in the country’s institutions. And it was in 2022, with the beginning of the “special operation” in Ukraine, that the propaganda meaning of “Putin equals Russia” became starkly apparent. As the Kremlin would have it, Putin’s war is Russia’s war, and by extension, a war involving all Russians—a fanciful notion that not only plays into the hands of regime propagandists but which has been readily embraced by many Western officials, as well. Of course, the real picture is far more complex. By now, the Putin majority has long since been taken as a given, and no one talks about it anymore. Instead, there is the pro-war majority, which supports the war partly by ignoring it in everyday life. As for the anti-Putin minority, the Kremlin’s long-standing habit of treating with contempt any who dare oppose the president has been transformed into a policy of active persecution and denunciation. Opposition and civil society figures themselves have been systematically discredited, exiled, and eliminated. Nonetheless, Putin still needs elections to give legitimacy to his eternal rule—and to his unending war. Thus, in March 2024, he will run for president for the fifth time since 2000. And as a result of the 2020 reform, it may not be the last, either. According to the changed constitution, Putin will able to run for office twice more—in 2024 and 2030—meaning that he could rule until 2036, when he will be eighty-three years old. For now, it seems clear that Putin is ready to make full use of that opportunity, at least in the coming vote. But this time, with the war in the background, there are new rules to the game, and both Putin and the Russian public know them. In exchange for keeping most of them out of the trenches, the passive majority of Russians will continue to support the government. And the elections—or rather, the mass approval of Putin’s activities—will show that the people, at least, are playing along. Ballots have become currency: Russians think that they can buy their own relative tranquility with them, even though there are no guarantees that Putin will keep his side of the bargain. JUST SAY YES Given the complete lack of alternatives to Putin, some of his supporters, such as the Chechen leader and fierce loyalist Ramzan Kadyrov, have proposed canceling the 2024 election altogether. Wouldn’t it be easier to forgo the vote, on the grounds that the country is at war, and that in any case, the Russian political field has been comprehensively cleared of competitors? Or why not elevate Putin to the title of supreme leader, national leader, or tsar, and then elect a formal president? But Putin really needs elections, at least in theory. In addition to refreshing his legitimacy, they serve as a way to show that the opposition—through the predictable landslide outcome—remains a tiny minority and cannot go against the overwhelming will of the Russian people. Moreover, by voting for Putin in 2024, Russians will legitimize his war. Even if the active phase of that war ends someday, it will still need to continue through permanent confrontation with the West and as a rationale for unrelenting repression, suppression, and censorship at home. Rather than elections, then, the March vote should be thought of as a kind of acclamation for the leader: they are simply voting yes to the only real choice available. Technically, this is a legitimate form of democratic expression, as enshrined in the constitution—and, apparently, in Russian history. (New textbooks for schools and universities discuss such Russian political traditions as the Novgorod veche, or popular assembly, in which everything was decided by shouting, approval, and acclamation by the crowd.) In other words, in the absence of any political competition, the regime has everything to gain from a fresh acclamation of its rule, and little to lose. Putin’s high numbers are guaranteed. Some will vote for him out of a sense of falsely understood civic duty, some will be coerced to do so at work: such is the general state of paranoia in today’s Russia that people sometimes take a smartphone picture of their completed ballot and send it to their bosses, after which they get the right to return to their private lives. Other votes may be falsified, including, perhaps, with the help of electronic voting systems. Still, deciding what content to fill the campaign with is another question. Obviously, it is essential for Putin to consolidate his narrative about the war. As Putin likes to say, “It was not us”: Russia was attacked by the West, and in response began a “national liberation struggle” to free Russia and other peoples enslaved by the West. And since Russians find themselves in a besieged fortress, they must give full support to their commander to repel both the enemy at the gates and the traitors and foreign agents within. By now, this logic has acquired the status of an axiom. Along with it comes a series of arguments—Russia is fighting for a “fairer multipolar world,” Russia is a special “state-civilization”—that justify the war, why it cannot end, and Putin’s rule itself. But what new element can be brought into the current election campaign, except, of course, an abstract declaration of peace and victory? STORIES ABOUT WHEAT In theory, the Russian public does not attach much significance to elections. In the minds of most people, there is simply no alternative to Putin, even if they think he is not particularly good. When Russians say “Putin,” they mean the president, and vice versa; like a medieval king, Putin has two bodies—one physical, one symbolic. Putin is the collective “we” of Russians, and voting for him every few years has become a ritual, like raising the flag or singing the national anthem on Mondays in high schools across Russia. But the war has added a new dimension to this rite. During the “special operation,” an unwritten agreement has been established between the people and their leader. The gist of this special relationship is that as long as the state refrains from dragging (most) people into battle, Russians will not question Putin’s authority. The partial mobilization in the fall of 2022 briefly called into question the state’s promise, but since then the authorities have largely solved the problem. Essentially, they have demobilized Russians psychologically, by maintaining and enforcing a pervasive normality. Thus, Putin himself has focused almost exclusively on domestic issues such as addressing economic problems and supporting artificial intelligence, staging meetings with young scientists and talented children. As a result, during the second year of the war, the general mood of the population has been much better, even despite rumors about another possible military mobilization after the election. One darker cloud has appeared over the Kremlin, in the form of open disgruntlement from families of the men who were mobilized in October 2022. These families are not seeking money, but they want to bring their sons and husbands home. They sense injustice, given that real criminals and brutal killers, who were pulled out of prison to fight in the war, have to serve for only six months before they can return as heroes, while their own sons have been given no reprieve. The government does not have a convincing answer to this challenge: Putin has long been used to fighting the intelligentsia and the liberal opposition, but here he is dealing with discontent from his own social base. These soldiers’ families have not yet coalesced into a formal movement or taken an explicit antiwar stance—a step that would be impossible because of the high level of repression. But every day these families have become more and more politicized. https://cdn-live.foreignaffairs.com/sites/default/files/styles/_webp_large_2x/public/images/2023/11/30/RTSO8BOD_e.jpg.webp?itok=yHfLNLyn For the bulk of the population, however, it is enough for the government to regularly tout the country’s economic health and income growth, and the mere fact that the country is not experiencing economic and social collapse is enough to convey an impression of business as usual. The Kremlin also continually highlights its foreign policy “successes.” In this imaginary world, Russia is supported in its confrontation with the West by the “global majority” in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. They are not just allies but countries for whom Russia is a ray of light in the gloom. It is assumed that anti-Western rhetoric and offers of economic assistance—or, as in the case of Africa, grain—will automatically lead the former satellites of the Soviet Union back to Russia. Meanwhile, official Russian media reports about military operations tend to emphasize the continual successes of “our guys” at the front. In these sunny accounts, there are no serious losses, only heroic behavior and victories. These briefings have come to resemble Soviet reports on agricultural achievements: the battle for the harvest is going well, and the only possible feeling can be one of satisfaction. From a Western point of view, these fantasy narratives seem unlikely to convince anyone. Surely, Russians must be sensitive to their growing isolation and economic hardship, and the ever-growing sacrifice of their young men at the front. But the Putin regime is not built upon active support. All it requires is the indifference of the majority, who mostly find it easier to accept the picture of the world that is imposed from above. By embracing the Putin story, they can retain a sense of moral superiority over a West that, they are told, is seeking to dismember their country, just as Napoleon, Hitler, and the “American imperialists” did in past decades. From month to month, Russian sociologists report broadly the same findings. Attention to events in Ukraine has stagnated; less than half of respondents say they follow the war closely, according to surveys by the independent Levada Center. On average, their support for the military remains high: about 75 percent of respondents say that they support the actions of the armed forces, including 45 percent who express “strong support.” On the other hand, surveys consistently show that slightly more than a half of respondents favor starting peace negotiations than continuing the war. But since the country has made large sacrifices in the fighting, most of those supporting a settlement would like to get something in return: Russia should keep the “new” territories it has conquered or “restored” to Moscow. BACK IN THE USSR Having reframed the “special operation” in Ukraine into a multidimensional war against the West, Putin has no particular urgency to talk about an endgame. In this sense, Putin’s goals for the war are no longer limited to returning Ukraine to Russia but now encompass what has become an existential rematch with the West, in which the Ukraine war is a part of a long, historically significant clash of civilizations. Putin sees himself as completing the mission begun by his historic predecessors, who were always forced to fight Western encroachment. In Putin’s new interpretation, even the Tatar-Mongol yoke—the two centuries of Russian subjugation that followed the invasion of Batu Khan, the grandson of Genghis Khan, in 1237—was not as harmful as Western influence and Western attacks. And since this is now an open-ended confrontation, the timeline for “victory” will necessarily extend far beyond the next decade. Ordinary Russians are receptive to ideas about the country’s historical greatness. As polling data have shown for many years, the main source of popular pride in the state today is the country’s glorious past. Russians have a special regard for their imperial history, especially the history of the Soviet Union, and an idealized image of the Soviet Union as a kingdom of justice has begun to emerge. At the same time, helped by acts of erasure by the Putin regime itself, Stalin’s repressions have receded from view or are sometimes considered as something inevitable and even positive. Among the Soviet achievements most remembered by Russians today, the greatest of all is the Soviet victory in the Great Patriotic War, as Russians refer to World War II. Accordingly, Putin has continually compared the “special operation” against Ukraine with the war against Nazi Germany. Thus, the celebrated soldiers and generals of the Great Patriotic War are the direct predecessors of today’s military, and by fighting in Putin’s war, Russians can again find redemption in heroic sacrifice. For example, in a speech before this year’s May 9 Victory Day parade, Putin suggested that the West was trying to reverse Russia’s historic victory. “Their goal,” he said, “is to achieve the collapse and destruction of our country, erase the results of the Second World War.” PEAK PUTIN? To make his worldview stick, however, Putin needs a viable economic model to sustain the mythmaking. In recent years, and especially since the start of the war, he has complemented his carefully cultivated distrust of the outside world by rejecting what he calls economic and technological “dependence” on the West. In practice, the Kremlin has been eliminating everything Western not through import substitution—which is impossible in a modern economy—but through a new dependence on China. Meanwhile, technology is becoming both more primitive and more expensive, which naturally puts the burden on the end consumer. Russia’s oil and gas resources—essential for sustaining the country’s extraordinary military expenditures—remain as important as ever. In a way, ideology is being used to make up for the shortfall in energy revenues, and to compensate for the gradual decline in the quality of life. Of course, the regime going to great lengths to maintain the impression that life goes on as normal, and to a degree, this is true: formally, in 2023, the country’s GDP and real incomes of the population are growing. But this is in large measure because of state injections into sectors serving the war and social payments to its participants. That growth is coming at the expense of the state, and it is unclear how long its resources will last. Risks of fiscal imbalance remain. A larger problem is the lack of an economic vision for the future. As the historian Alexander Etkind notes, “A resource-dependent state is always afraid of the raw materials running out, but the biggest threat of all comes from new technology that makes those materials unnecessary.” Putin has never believed in the energy transition or green economy, but by insisting on preserving Russia’s existing technological structure and petrostate model, his regime has impeded modernization in both a technological and political sense. As a result, the oil and gas economy is not being replaced by a more sustainable model. Notably, some of the countries in the east that are now consuming Russian raw materials may be shifting their energy mix in the future: in time, for example, China may have less demand for Russian energy. But Putin’s autocracy does not care about future generations, much less the environment. Alongside its dependence on nonrenewable fossil fuels, the Kremlin tends to treat human capital as another expendable commodity. But that does not make the human supply chain any cheaper. On the contrary, it is becoming more expensive: professional soldiers, mercenaries, volunteers, family members of the dead and wounded, and the workers who man Russia’s military-industrial complex (and of which there is currently a grave shortage) must all be paid. Hence, the government has had to reconcile itself to an inexorable growth of wages and social benefits. People’s incomes are growing not because of economic development or advances in the quality of the labor force but simply so the government can sustain hostilities and fuel the continued production of lethal weapons. For now, the state budget is still balanced, but budget discipline is in a permanent danger because of the state’s chosen priorities. By paying more for defense and security, Russia has fewer resources for people and their health and development. In the Putin economic model, more spending on death means that there is less to spend on life. SWAN LAKE So what will Putin’s election campaign look like? Given the current situation, Putin can only offer the public the same model of survival that has become standard since the “special operation” began: to live against the backdrop of war without paying attention to it and wait for “victory” in whatever form the president someday chooses. Again, it is unlikely that that choice will be clearly defined during the election season. The war itself has become a mode of existence for Putin’s system, and there is little reason to expect that it will end any time soon, since that could undercut the urgency of supporting him. In any case, during periods of peace, Putin’s ratings have often stagnated, whereas they have soared during moments of military “patriotic” hysteria such as the Georgian war of 2008 and the Crimea annexation. The “special operation” has been no exception. Moreover, for now, war fatigue has not yet translated into serious discontent or a decrease in support for the regime. According to the Levada Center, popular support for Putin, as well as for the war and the military, has remained broadly stable, with Putin maintaining around an 80 percent approval rating. In theory, then, the indifference of the pro-war majority suggests that Putin can continue the war for the indefinite future. The Kremlin’s other option would be to ramp up hostilities, including a new mobilization, whether partial or general, combined with further distancing from the West and more repression at home. But such changes could rock the Kremlin, which at some point risks colliding with an iceberg of extreme public anxiety and a deteriorating economy. Russia’s underlying problems are not going anywhere, and have been slowed down only by the relatively rational actions of the government’s economic managers. Accordingly, maintaining the status quo seems the most likely path forward. During periods of peace, Putin’s ratings have stagnated. When Russians go to the polls in March, Putin can count on high voter turnout and continued passive support for the war. Most of them have very low expectations: they have long lived according to the mantra “The main thing is that it shouldn’t get even worse.” But the fresh acclamation of the regime that the election will doubtless bring will not necessarily provide a mandate for truly drastic moves such as the full closure of Russia’s borders or the use of nuclear weapons. Indeed, as the Kremlin must understand, the outcome will be less a mandate for radical new changes than a signal that it can continue much as before. How long can a country exist in this state of passive and unproductive inertia? Theoretically, Putin could reap advantages by continuing the war but at the same time keeping the population calm, thereby outlasting the West with its supposedly flagging interest. But there are several reasons to question this assumption: first, it is not only Ukraine and the West but also Russia whose resources are being dramatically depleted. Second, surprises are possible, such as the growing wave of discontent among the Russian mobilized soldiers’ families. Even if it does not result in a broader political backlash, the phenomenon has already shown that black swans of different sizes can come from unexpected places at unexpected times. But where are the redlines that show just how far resources can be depleted and the patience of various sections of the population be tested without triggering a larger collapse? Do these limits even exist in Russia? So far, with a few minor exceptions, everything points to the fact that they do not. Moreover, no matter how much the regime has tightened its grip, change of leadership is not a priority for the Russian public: on the contrary, polls and focus groups show that many people fear a change at the top. Still, Russians are not ready to die for Putin. In 2018 and 2020, Putin’s ratings fell because of an unpopular decision to increase the retirement age, and then because of the effects of the pandemic; it is possible that his base of support will take other hits in the coming months. Indeed, in the mood of both the public and the elites, there is an invisible yet discernible expectation of such events. For most, however, the yearning is more basic. They desire to end “all this”—meaning get rid of war—as quickly as possible and begin to live better, more safely, and more peacefully. But it is unlikely that this will happen without regime change. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/russian-federation/putins-war-party View Quote Why would any rational person believe any Russian government report of vote count? |

|

|

|

|

Originally Posted By Capta: Something I bet that both sides are doing is laying these surface minefields to cover a lot of space with limited manpower, but then also laying buried minefields. So they clear the obvious minefield using drone spotting, then run over another minefield they didn’t know about. View Quote Yes. I believe that. Intentional or otherwise, minefields on top of minefields... |

|

|

|

|

Originally Posted By Ryan_Ruck: So... Not "light damage"?  View Quote View All Quotes View All Quotes Originally Posted By Ryan_Ruck: Originally Posted By AlmightyTallest: lol, official word is that it will indeed not buff out.

https://pbs.twimg.com/media/GAz3yR1XEAABzyN?format=jpg&name=small So... Not "light damage"?  They can probably salvage the data plate and rebuild it from there. |

|

|

|

|

Originally Posted By AlmightyTallest:

View Quote They’ve nailed a substantial number of TOS-1s in the Kherson region. Memory says it’s 8-10 in the last month or so, and they didn’t have that many to start with. I don’t think that one will buff out. |

|

|

|

|

Originally Posted By AlmightyTallest:

View Quote That was crazy skill! |

|

|

|

|

Originally Posted By AlmightyTallest: 10 minutes of Magyar FPV drone attacks. no translation.

View Quote JAGGA JAGGA NEEDS NO TRANSLATION |

|

|

|

|

ISW assessment for December 8th.

https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-december-8-2023 |

|

|

It's not stupid, it's advanced!!

|

|

Who has the Russian ban on the church link? Can’t find it

|

|

|

connoisseur of fine Soviet armored vehicles

Let's go Brandon President of the Volodymyr Zelenskyy fan club |

|

Originally Posted By realwar: Russia threatens military strikes on Western countries if Ukraine's newly-donated F-16s are based in NATO territory Video https://i.dailymail.co.uk/1s/2023/12/08/16/78741569-12842177-Maria_Zakharova_spokeswoman_for_the_Russian_foreign_ministry_war-a-15_1702053835303.jpg Russia has threatened to target Western countries with missile strikes if Ukraine's newly-donated F-16 fighters are based in NATO territory. Such an act by Vladimir Putin would also certainly trigger a World War Three scenario between the West and Russia. It comes as the Kremlin warned today that a nuclear world war is closer than at any time since the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962. Maria Zakharova - spokeswoman for the Russian foreign ministry - warned the West that the advanced F-16 fighters delivered to Ukraine will be a fair target for Russia if they are based in NATO countries. She said that the fourth-generation fighter jets could be based in Poland, Slovakia and Romania, meaning NATO is 'getting deeper' into the Ukrainian conflict. 'There have been many questions asked about the transfer of F-16 fighter jets to Ukraine,' said Zakharova, 47. She continued: 'I would like to say that NATO member states continue, as you understand, to intensively arm Ukraine and the supply of tactical fighters is next. 'Given the fact that a significant part of Ukraine's airfield infrastructure has been destroyed, it is possible that these American fighters will be based outside the country, in Poland, Slovakia and Romania. 'Thus, the North Atlantic Alliance is getting deeper and deeper into the Ukrainian conflict.' In August, the United States approved sending F-16 fighter jets to Ukraine from Denmark and the Netherlands to defend against Russia. They are expected to arrive in Ukraine next year. Holding the rank of Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary, Zakharova is Russia's most senior woman diplomat and issued a specific threat to NATO countries on behalf of her boss, Putin's hawkish 73-year-old Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov. Zakharova continued: 'The West is waging a hybrid war against our country under the slogan of saving Ukraine. 'At the same time, they also agreed that their main goal is to prevent confrontation with Russia. 'Funny. In reality, the risks of a direct military clash between Russia and NATO are only increasing. 'For the Russian armed forces, fighters participating in the conflict on the side of the Ukrainian Armed Forces, no matter where they fly from, will be a legitimate target for destruction.' Her blast coincides with a warning from the deputy head of the Russian security council, Dmitry Medvedev, a former Kremlin president and prime minister. 'Never since the Cuban Missile Crisis has the threat of a direct clash between Russia and NATO leading to the Third World War been so real,' he said. More than 21 months into the biggest conflict in Europe since World War Two, fighting rages on in Ukraine with no end in sight and neither side has landed a telling blow on the battlefield. Ukrainian soldiers, living in freezing trenches, acknowledge they are exhausted going into a second winter of full-scale war with a resource-rich, nuclear-armed superpower that has more than triple Ukraine's population. Continued View Quote That’s interesting because I’ve never seen any indication whatsoever that Ukraine’s F-16s would be “based in” a NATO country, |

|

|

|

|

Originally Posted By Prime: This is allegedly an image of an Su-57 taking a smoke break. https://pbs.twimg.com/media/GA2TFmGWAAA1SnX?format=jpg&name=large https://twitter.com/TreasChest/status/1733203160116699544 View Quote They've only got like 8 of them... From the looks of that, maybe 7 now. |

|

|

|

|

Originally Posted By RockNwood: I especially enjoy seeing those heavy rocket systems droned. They are short range and have no business getting close enough to pummel cities and towns into moon dust. I hope a lot of Russian operators get to enjoy the thermal aspects. View Quote View All Quotes View All Quotes Originally Posted By RockNwood: Originally Posted By AlmightyTallest:

I especially enjoy seeing those heavy rocket systems droned. They are short range and have no business getting close enough to pummel cities and towns into moon dust. I hope a lot of Russian operators get to enjoy the thermal aspects. Yeah that thing was moving and it brewed right up. Three more Russians receiving their just wages. |

|

|

|

|

Originally Posted By Capta: That’s interesting because I’ve never seen any indication whatsoever that Ukraine’s F-16s would be “based in” a NATO country, View Quote It is the Russian conjecture that they have bombed all of Ukraine's airbases and airports and runways to such an extent that it will not be possible, or at least not viable, to base "delicate, finicky western" F-16s anywhere inside the country. It might also be a play to justify attacking the F-16s in NATO countries as they're being ferried in, prior to delivery? |

|

|

Slava Ukraini! "The only real difference between the men and the boys, is the number and size, and cost of their toys."

NRA Life, GOA Life, CSSA Life, SAF Life, NRA Certified Instructor |

|

Field grade officer in the Ukebro Army

|

|

Originally Posted By Prime: https://pbs.twimg.com/media/GA1RfA1W8AABSoX?format=jpg&name=small Yan Petrovsky, a militant of the neo-Nazi Group "Rusich," will be deported to Russia from Finland. Finnish border guards have detained neo-Nazi militant and co-founder of the Russian sabotage-assault group "Rusich" Yan Petrovsky at the exit from Vantaa Prison, the Helsingin Sanomat newspaper reported. Earlier, the Supreme Court of Finland ruled that Petrovsky could not be extradited to Ukraine, where he is suspected of forming a terrorist group, because he could allegedly face torture in a Ukrainian prison, and called for his release. In August, Petrovsky, with a passport in the name of Voislav Torden, was detained by the Finnish Border Guard agency while trying to fly to Nice, following an extradition request from Ukraine. "Rusich" group is fighting on Russia's side in Ukraine. Petrovsky was one of its commanders. He became famous for posing in front of the corpses of Ukrainian soldiers. Since 2004, "Slavyan" lived in Norway, but in 2017, he was stripped of his residence permit and deported. In September 2022, the United States imposed sanctions on him.

View Quote Smells like a bribe. “He may be tortured in Ukraine…”. Based on what evidence? His Russian attorney’s speculation and payout? |

|

|

Deplorable fan of liberty

“I don’t need a ride, I need more ammunition.” |

|

Originally Posted By fadedsun: Who has the Russian ban on the church link? Can’t find it View Quote Russian occupation authorities ban UGCC |

|

|

|

|

INTERVIEW WITH IGOR STRELKOV TO THE BAZA NEWS AGENCY